What is

IQ?

Introduction to IQ

Measuring Intelligence – Noteworthy Contributors

IQ Tests Today

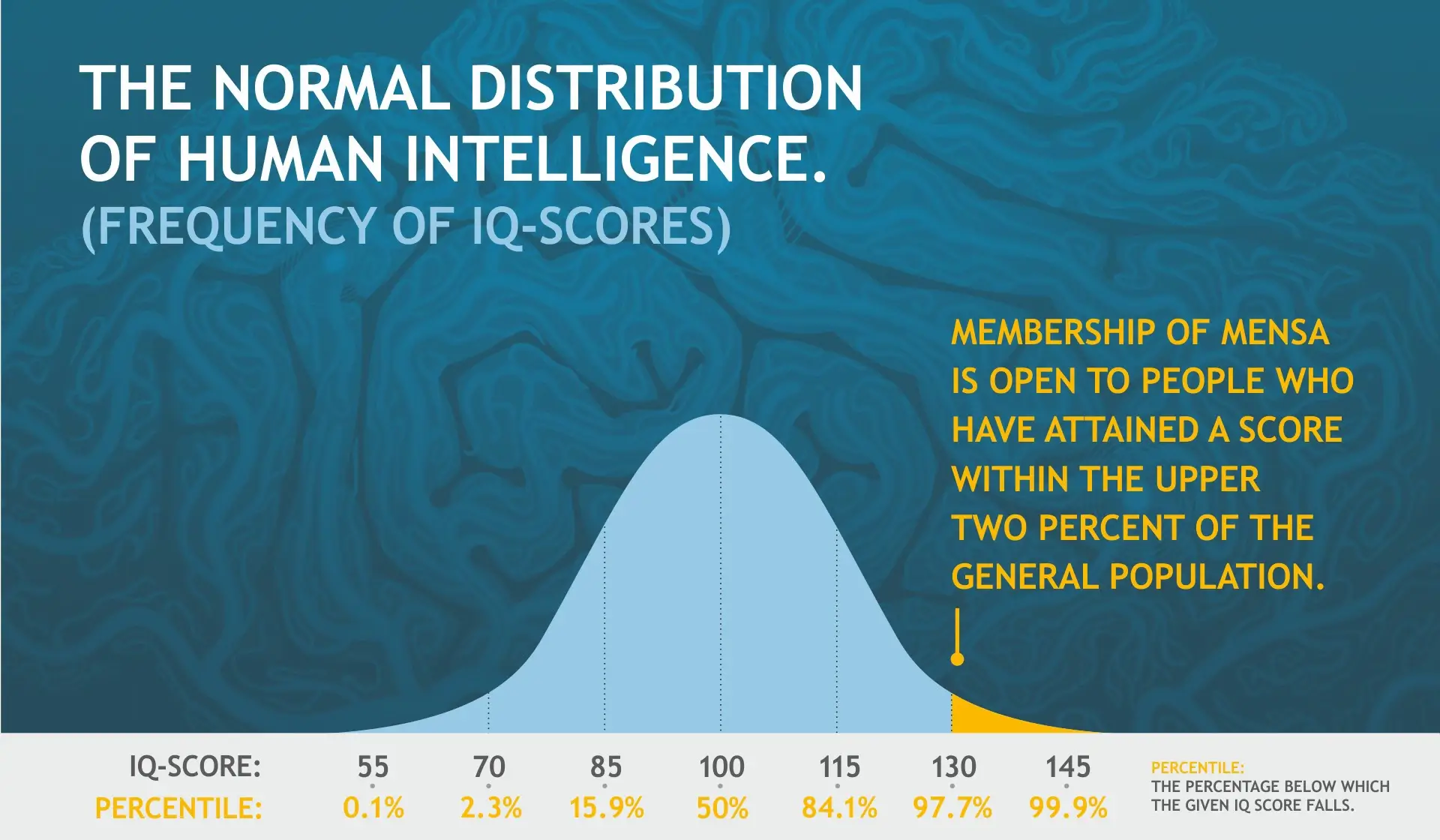

IQ is a type of standard score that indicates how far above, or how far below, his/her peer group an individual stands in mental ability.

The peer group score is an IQ of 100; this is obtained by applying the same test to huge numbers of people from all socio-economic strata of society, and taking the average.

The term ‘IQ' was coined in 1912 by the psychologist William Stern in relation to the German term, ‘intelligenzquotient’

At that time, IQ was represented as a ratio of mental age to chronological age x 100. So, if an individual of 10 years of age had a mental age of 10, their IQ would be 100. However, if their mental age was greater than their chronological age (e.g., 12 rather than 10), their IQ would be 120. Similarly, if their mental age was lower than their chronological age, their IQ would be lower than 100.

When current IQ tests were developed, the average score of the norming sample was defined as IQ 100; and standard deviation (a statistical concept that describes average dispersion) up or down was defined as, for example, 16 or 24 IQ points greater or less than 100.

Mensa admits individuals who score in the top 2% of the population, and they accept many different tests, as long as they have been standardised and normed, and approved by professional psychologists’ associations. Two of the most well-known IQ tests are ‘Stanford-Binet’ and ‘Cattell’ (explained in more detail below). In practice, qualifying for Mensa in the top 2% means scoring 132 or more in the Stanford-Binet test, or 148 or more in the Cattell equivalent.

Sir Francis Galton was the first scientist who attempted to devise a modern test of intelligence in 1884. In his open laboratory, people could have the acuity of their vision and hearing measured, as well as their reaction times to different stimuli.

The world’s first mental test, created by James McKeen Cattell in 1890, consisted of similar tasks, almost all of them measuring the speed and accuracy of perception. It soon turned out, however, that such tasks cannot predict academic achievement; therefore, they are probably imperfect measures of anything we would call intelligence.

The first modern-day IQ test was created by Alfred Binet in 1905. Unlike Galton, he was not inspired by scientific inquiry. Rather, he had very practical implications in mind: to be able to identify children who could not keep up with their peers in the educational system that had recently been made compulsory for all. Binet’s test consisted of knowledge questions as well as ones requiring simple reasoning. Besides test items, Binet also needed an external criterion of validity, which he found in age. Indeed, even though there is substantial variation in the pace of development, older children are by and large more cognitively advanced than younger ones. Binet, therefore, identified the mean age at which children, on average, were capable of solving each item, and categorized items accordingly. This way he could estimate a children’s position relative to their peers: if a child, for instance, was capable of solving items that were, on average, only solved by children who were two years older, then this child would be two years ahead in mental development.

Subsequently, a more accurate approach was proposed by William Stern, who suggested that instead of subtracting real age from the age estimated from test performance, the latter (termed 'mental age') should be divided by the former. Hence the famous 'intelligence quotient' or 'IQ' was born and defined as (mental age) / (chronological age). It indeed turned out that such a calculation was more in line with other estimates of mental performance. For instance, an 8-year-old performing on the level of a 6-year-old would arrive at the same estimate under Binet’s system as a 6-year-old performing on the level of a 4-year-old. Yet, in Stern’s system, the 6-year-old would get a lower score as 4/6 < 6/8. Experience shows that when they both turn 10, the now 8-year-old is more likely to outperform the now 6-year-old in cognitive tasks; hence Stern’s method proved to be more valid.

It was in the US where IQ testing became a real success story after Lewis Terman revised Binet’s test, creating a much more appropriate norm than the original, and he published it as the Stanford-Binet test (Terman was a psychologist at Stanford University). He was also keen to multiply the result by 100, so the final equation for IQ is (mental age) / (chronological age) X 100. Indeed, an IQ of 130 sounds much cooler than an IQ of 1.3.

This method, however, only works well in children. If a child’s parents were told that their 6-year-old already had the mental capabilities of an average 9-year-old and, therefore, his or her IQ was 150, they would be over the moon. But if the child’s grandfather was told that even though he was only 60, his cognitive abilities were on a par with the average 90-year-old, he might not take it as a compliment. Obviously, the quotient only works as long as Binet’s original criterion is functional; i.e., as long as older age in general means better abilities. In other words, the method is inappropriate when mental development does not take place any more.

David Wechsler solved the problem of calculating adult IQ by simply comparing performance to the distribution of test scores, which is a normal distribution. In his system the IQ of those whose score equalled the mean of the age group was 100. This way the IQ of the average adult would be 100, just like the IQ of the average child in the original system. He used the statistical properties of the normal distribution to assign IQ scores based on the extent of the contemporaries one outscored. For instance, someone whose score was one standard deviation above the mean, and who thus outperformed 86% of his or her contemporaries, would have an IQ of 115, and so on.

IQ Tests Today

So, why is it called 'IQ', a quotient, if nothing gets divided? The simple reason is that the concept of IQ had become too popular for the term to be discarded. Even so, it is interesting to note that in adults it is not really a quotient at all: it is an indication of how well one performs on mental tests, compared to others. Besides extending the concept of IQ, another major step in the development of IQ testing was the creation of group tests; before this, people had been individually tested by qualified psychologists. The first group test was created for the US army, but they soon spread to schools, workplaces and beyond, becoming one of psychology’s greatest popular successes, and remain so to this day.

IQ Tests Today

So, why is it called 'IQ', a quotient, if nothing gets divided? The simple reason is that the concept of IQ had become too popular for the term to be discarded. Even so, it is interesting to note that in adults it is not really a quotient at all: it is an indication of how well one performs on mental tests, compared to others. Besides extending the concept of IQ, another major step in the development of IQ testing was the creation of group tests; before this, people had been individually tested by qualified psychologists. The first group test was created for the US army, but they soon spread to schools, workplaces and beyond, becoming one of psychology’s greatest popular successes, and remain so to this day.